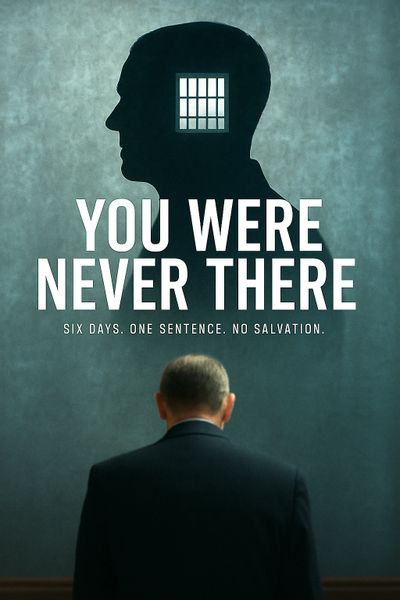

You Were Never There

Welcome to Mylo Sticky Studio Short Stories

They sent another preacher to talk to him. Number fourteen, by his count. This one had soft eyes and hands that looked like they’d never thrown a punch. He carried a Bible tucked under his arm like a bandage he wasn’t sure how to use. The killer sat on the other side of the glass, hands cuffed in front of him, motionless. He looked like a man trying to remember what hunger used to feel like. His face was lean, skin too tight on bone, and his voice was quieter than it should have been.

“You’re number fourteen,” he said.

The preacher tilted his head. “Fourteen what?”

Killer smiled without warmth. “God’s errand boys. Chaplains. Shepherds of the damned. You all show up at the end. It’s funny. Nobody gave a shit when I was eight and killing stray cats in alleyways. But now? Now you’re lining up like I’m a final exam.”

“I’m not here to judge you,” the preacher said, gently.

“No,” the killer said, “you’re here to understand me.”

A pause. Silence, save for the low hum of fluorescent lights and the faint shuffle of guards behind the mirrored glass. The killer leaned forward, the metal of his cuffs whispering against the tabletop.

“I’ll save you some time,” he said. “I did it. All fifteen. And not once did I feel anything.”

The preacher didn’t flinch. He just waited.

“Not the first one,” the killer continued. “Not the girl behind the diner. Not the woman with the red scarf. Not the librarian. Not the one who cried so hard she puked.”

He looked down at his hands, as if trying to find the echoes of blood. “I waited,” he whispered. “After the first time, I sat in the dark for hours. I thought… maybe now I’ll feel it. The voice. That tug in your gut. That breath that says ‘stop, you monster.” He looked up, eyes glassy but sharp. “It never came.”

The preacher shifted slightly, folding his fingers over the edge of the Bible. “Some people bury that voice. Push it down until it can’t breathe. Until it’s too quiet to hear.”

“That’s the difference,” the killer said. “I didn’t bury it. I never had it.” He said it plain, like a man stating the weather, as if he was noting something everyone else missed.

“You all talk about conscience like it’s a given,” he went on. “Like it’s part of the kit when you're born. Like two eyes, ten fingers, and the little voice that tells you not to throw a brick through someone’s skull.” He shook his head, a dry laugh catching in his throat. “But mine was never there. It wasn’t sleeping. It wasn’t hiding. It was absent. I was a house built without walls. Just wind blowing through the damn thing.”

“You think you were born evil,” the preacher said quietly.

“No,” the killer said. “I think I was born alone.”

The preacher didn’t answer. Maybe he couldn’t. The killer looked past him, to the spot where the wall met the ceiling, where dust gathered and light tried to pretend it meant something.

“I used to wonder,” he said. “If maybe that voice - my conscience, my soul, whatever you want to call it - was supposed to be a person. A brother, maybe. A twin that never made it. Or a guardian meant to step in when the switch flipped.” He leaned in again. This time, his voice was low, hoarse. “But he never showed up. Not when I crushed her windpipe. Not when I left the body in the river. Not when I watched the news and saw her face next to the word missing.

He paused. Swallowed. “Where the hell were you?”

The preacher blinked. “What?”

“You. The voice. The presence. The hand on my shoulder. The breath that should’ve said ‘no.’ Where were you? You want to talk to me about God? Then tell me where the hell He was when I needed Him most.”

“You don’t get to blame God,” the preacher said, and his voice cracked - not with anger, but heartbreak. “You don’t get to turn your sins into a question of divine attendance.”

“I’m not blaming anyone,” the killer said. “I’m just keeping inventory.”

He sat back, cuffs clinking again, and for a moment, he looked small. Smaller than any of them expected. “I know what I am,” he said. “Fifteen women are dead because something in me was supposed to say stop. And it didn’t. It never did.”

He looked at the preacher then, with something close to…not sorrow, but a strange kind of pity. “And now you come in here, with your book and your faith, asking me if I’m ready to repent like it matters. Like, I can be fixed in the final hour. But let me ask you something, preacher.”

His voice dropped to a whisper. “Where the hell was my conscience after the first one?”

<->

The preacher stayed long after the guards expected him to leave. Shift change came and went. Somewhere down the hall, someone coughed, and the buzz of a vending machine filled the silence like background static.

The killer leaned his forehead to the glass, eyes half-closed, voice barely a thread. “I tried to build the voice myself,” he said.

The preacher didn’t respond. He just sat with the weight of it all. His Bible was still on his lap, unopened.

“I tried after the third one,” the killer murmured. “I thought maybe if I pretended hard enough - if I acted like I had a conscience - it would grow inside me like a callus. I lit a candle. Said a name. Pretended to be sorry.” He chuckled, soft and bitter. “But there was nothing to grow around. No wound. No root. Just… ash.”

The preacher’s voice came quietly. “You said before that you were born alone. That voice never showed up. What if… what if it did? What if it was there, but buried under everything else?”

The killer looked at him, and for the first time, the mask cracked - just slightly. Not in fear. Not even anger. Just a tired sort of grief, like a man who'd searched every corner of the house and still hadn’t found the ghost.

“Don’t,” he said. “Don’t do that. Don’t dress this up in maybe’s.”

“I have to,” the preacher said. “Because if I admit that you were born without it - that something never came - then I have to question everything I believe.”

He stood, pacing now. The first sign that this visit wasn’t just for the killer’s salvation. “If the soul doesn’t come standard,” the preacher said, “then what else doesn’t? Kindness? Empathy? Hope? If you’re telling the truth, then we’re all just a roll of the dice away from becoming you.”

The killer nodded, slowly. “Now you’re catching on.” He leaned back, metal cuffs sliding with a dull rattle. “That’s the real horror, preacher. Not that I’m a monster. But that I’m a reminder. That I'm what it looks like when you never show up.”

The preacher turned sharply. “Me?”

“You. Conscience. God. Whatever name you want to put on it.” He tapped his temple. “You were supposed to be in everyone. And maybe in most folks, you are. But not in me.”

The preacher sank back into his chair, spine folding like wet cardboard. The line hung in the room like smoke - you were never here - and for a moment, it wasn’t clear who the words were for anymore. “I used to believe,” the preacher said quietly, “that if you go deep enough into a person, past the fear and shame and guilt, you’d find a spark. Something divine.”

He looked up at the man across from him, the killer. “But when I look at you, I see… a mirror with nothing behind it.”

The killer smiled, slow and wide. “Exactly.”

They sat in silence for a long time. Then the guard tapped on the glass. “Time.”

<->

The room was too clean. Too cold. Like death had been sterilized and filed under Procedure. They strapped the killer down. He didn’t fight. Didn’t speak. Just looked up at the ceiling like he expected to see something. The preacher stood at the observation window. Alone now.

A voice called out, “Any final words?”

The killer licked his lips. His voice was calm. Confessional. “If you’re out there - whatever you are - just know…” He smiled, sad and wide and cruel all at once. “You create me like this.”

The syringe plunged. The body stilled. The silence that followed didn’t feel holy. It felt like confirmation.

<->

The chapel office was dim, lit only by the last strokes of a bruised sunset and a crooked desk lamp. Dust floated in lazy spirals above the wooden floor. Books lined the walls - some read, some untouched, most marked by time and use. The preacher sat across from his superior, a man with silver hair, his hands clasped in front of him, as if he were used to holding things that might break.

“So,” the senior pastor said, “you sat with him.”

The preacher nodded.

“And?”

Preacher hesitated. Not because he didn’t know what to say, but because he did. Every word of it. It had been built since the glass wall, since the dead stare, since that final sentence that still echoed in his bones. “I couldn’t find God in him,” the preacher said.

His voice wasn’t angry. It was something far more dangerous. Fractured.

“He wasn’t wrestling with sin. He wasn’t hiding from guilt. He wasn’t lost, or broken, or angry at heaven.” Preacher looked up, eyes hollow with revelation. “He was empty. Like a house built without a front door. Like someone forgot to finish him. Like he was waiting his whole life for a voice that never arrived.”

The older man frowned, slowly folding his hands tighter. “He said… God was never there?”

“No,” the preacher said. “He didn’t say it. He showed it.” Preacher stood up, pacing now, the first sign of motion since he entered. “He said he waited for that whisper inside. That tug of guilt. That thing we all feel when we’re about to do something awful.”

He paused, hands out like he was holding something invisible and heavy. “And it never came. Not once. Not ever.”

Silence. The older man didn’t move.

“I know we talk about free will,” the preacher said. “About people choosing darkness. But what if someone like him never had light to begin with? What if there wasn’t a choice?” He stopped pacing. Leaned on the windowsill. “I looked into his eyes, and I didn’t see a man battling temptation. I saw a man who’d never been introduced to it in the first place. A man who built a life without a compass, because the compass was never issued.”

He turned around, slower now. “And I left that room with a question I can’t shake.” His voice trembled. “What kind of God makes someone… and forgets to put the soul in?”

A long silence. The older man didn’t answer. Maybe he couldn’t.

The preacher sat back down, quieter now. “I used to believe that everyone had a spark. That even the worst among us carried a flicker of God’s breath inside them.” He looked at the floor, his fingers curled as if he wanted to pray but had forgotten how. “But now I’m not so sure.”

Outside, the sun vanished behind the trees. The room went dim, like even the light had given up. The preacher closed his eyes.

“He kept saying it, over and over again, right up until the end.” His voice dropped to a whisper. “You were never really here.”

THE END